A Yoga Break-up

This essay was originally written and posted in 2016, around the time that I sold the Shala. When I wrote this, I couldn’t have foreseen the public reckoning that would later unfold around Pattabhi Jois and the Ashtanga community—an acknowledgment, still incomplete, of the harm caused by abuse and the complicity that allowed it to continue. My own experience was not one of sexual assault, but it was shaped by the same dynamics of authority, exclusivity, and misuse of power that have caused deep and lasting harm within yoga communities. That awareness inevitably changes how I read this piece now.

From my trip to Mysore in 2009.

Background:

In November 2015, our small Mysore program at the Yoga Shala suddenly split into two groups when one group decided to open a new studio, essentially replicating what we were already offering. They justified the separation by claiming to be more “traditional” and needing independence to pursue their vision of yoga.

The effects of this division reached far beyond those directly involved—myself as the studio owner, the departing teacher, and the other instructors. The wider community of practitioners, many unaware of the full story, were suddenly asked to choose sides. This created confusion and a palpable sense of loss. The morning energy that once carried us through the pre-dawn cold now felt scattered. A quiet sentiment of “if you’re not doing it, I’m not doing it” hung in the air.

Such an abrupt energetic shift has shaken the ground beneath me, reminding me that disruption—however painful—is also part of life’s unfolding.

I wrote this article first for myself, and also for you—if you’re part of our community and wondering what happened. I wrote it, too, for anyone interested in my reflections on what we’re really doing each time we unroll our mats.

One of my enduring interests is seeing yoga live up to its full potential for anyone drawn to its breath, its movement, and its stillness. I choose not to be exclusive in how I meet people where they are. There is more than one way to do something, and our bodies are not all meant to move the same way.

I have other motives as well. In my experience, divisions like this reveal why the teaching of yoga postures remains a fledgling profession—one that too often loses sight of what’s possible. Part of the problem lies in how charismatic personalities, appealing to our insecurities, use anecdotal “truths” to justify their own agendas. But I digress. I believe we can do better.

Modern postural yoga as a modern solution to many of todays societal and health care crises is right at the tip of our hasta’s and pada’s. Let’s be done with the question over who is more authentic, more traditional, more sattvic (pure), or more spiritual and get busy helping people breathe better, move better and feel better. So here goes…

My head is full of snippets of words that have stuck with me. Things like an ex-boyfriend who once told me that I “wasn’t spiritual enough.” And my thought afterward; he might be right, but how does he know?

When I opened my own yoga studio in 2003, eight months pregnant with my first, my Dad said, “Katie, the people who make it in small businesses are those with a can-do attitude.” Can-do, Can-do, Can-do, Can-do… got it.

My first teacher in Boston taught me everything I know about running a yoga school, Mimi (Louriero) she also told me, “Katie, you have to think for yourself, trust yourself, and stop trying so hard to please everyone.” If only I could have listened to her way back then.

From Mimi I learned an ashtanga that was inclusive and had ease and care woven into the vinyasas and postures. She was supportive of each of her students and attended to our differences with skill. She instilled an open atmosphere and we all regularly went to other schools like Jivamukti in NY, and Iyengar workshops at Patricia Walden’s place down the street, classes at Baron’s in Porter Square, Bikram yoga, and yoga therapy, we supported other yoga teachers, studied the sutras and tried to eat well. It was just yoga.

But karmically, or ancestrally, I needed something else. Like so many others desensitized by anxiety, depression, PTSD, eating disorders, addiction, trauma, grief… I was uncomfortable inside, so I was uncomfortable with anything easy if I thought there was something else harder, I wasn’t enough.

Knowing that there was something more was my comfort zone. The levels, the progression, the discipline, and the uniformity of another ashtanga called out to me. So did the rituals and belonging. I was drawn toward the transcendental aspect of yoga. In Vedanta, a non-dual perspective that the individual soul is intrinsically yoked with God. Where there is transcendence of the mortal coil, the body, in order to reach self- God - realization. I didn’t exactly know what I was signing up for.

It is said that you find your teacher when you are ready for him or her. So I found the authoritative energy I knew how to show up for, and a decade of another ashtanga that was full of devotion, rules, the bells and smells I was looking for; chanting, beautiful Sanskrit, and highly charged and energized complex postures. The physical part often resembled the dynamics of elite level rowing for a former West German coach in a competitive atmosphere. The mental and emotional part felt like I was doing something really special, one that only those of us with the character to handle it could do, and one that challenged me and left my mind sometimes quiet from exhaustion.

Do people who are extreme need more extreme? In our panchakarma cleanse we doing right now, which I will tell you about later, Erin told us that a tenant in Ayurveda is that like increases like, and opposites decrease each other. This is why we often crave what isn’t actually good for us. So it would seem the answer is no, extreme people probably don’t need extreme.

So as I was immersed in this one way of ashtanga, and my can-do attitude in tact, I started to notice the injuries, and the lack of efficacy of the full sequence of postures in certain body-minds trying to fit into its’ mold. I went to India to study in Mysore to see if there was a different ashtanga I was missing, one that was more therapeutic, (wasn’t the Primary Series supposed to be Yoga Therapy?) Also that same year I went to India, I started a training program in a neuromuscular body-mind re-education method called Hanna Somatics. In Mysore I made a lifelong friend, and enjoyed Sanskrit lessons, but other than that left questioning what are we doing here?

Later, from Tom Hanna, I got this quote, “The human body is not an instrument to be used, but a realm of one’s being to be experienced, explored, enriched and, thereby, educated”.

And for some reason, finally, I started to listen.

You see, I teach yoga to help people heal themselves, by finding balance within, by moving more freely (so they can do the things they want to do in their lives). The dean of my master’s program said this in a presentation the other day, “Ethically, a physician’s preference toward a certain modality does not justify the use of that modality, if the potential for another therapeutic intervention to have a better outcome is known.” It became unethical for me to push people into yoga postures for the sake of a sequence. I could not keep teaching that ashtanga anymore.

And so my ashtanga began to shift. In his blog, When Yoga Empowers, J. Brown calls what I’ve gone through a shift from a transcendental to the sacrosanctual. Brown says this about the transcendental perspective: “Before the skills and knowledge required to obtain the ultimate goal of realization are bestowed upon the selfless devotee, the student is made worthy through rigorous austerities”. By rigorous austerities, unless you are also walking on coals, he means more and more advanced yoga postures. Let me ask you the same question Matthew Remski asked me recently, “When you are doing these extreme postures are you getting more self-realized?” My answer was no. And actually the exact opposite for me, because telling my body to do something, even if I am really good at telling my body to do something, is inherently opposed to listening to the whispers and sometimes screams that is the language of my changing flesh and bones. For myself, I need to say this again, telling my body what to do is very different than listening to my body has to say.

And… I stayed at the party for too long… damage accumulating in my joints began making pretty much anything where I had to put weight on my hands painful enough that even I couldn’t ignore it. As Tracy Hodgemen describes in her blog, “it was like I was sliding down a mountain I had worked so hard to climb.” Though I was sort of ready to slide down the mountain of postures, I wasn’t ready to lose my teacher, my identity, friends and quite frankly, my livelihood. I wasn’t ready to be judged and labeled and then ostracized for not being ashtanga enough.

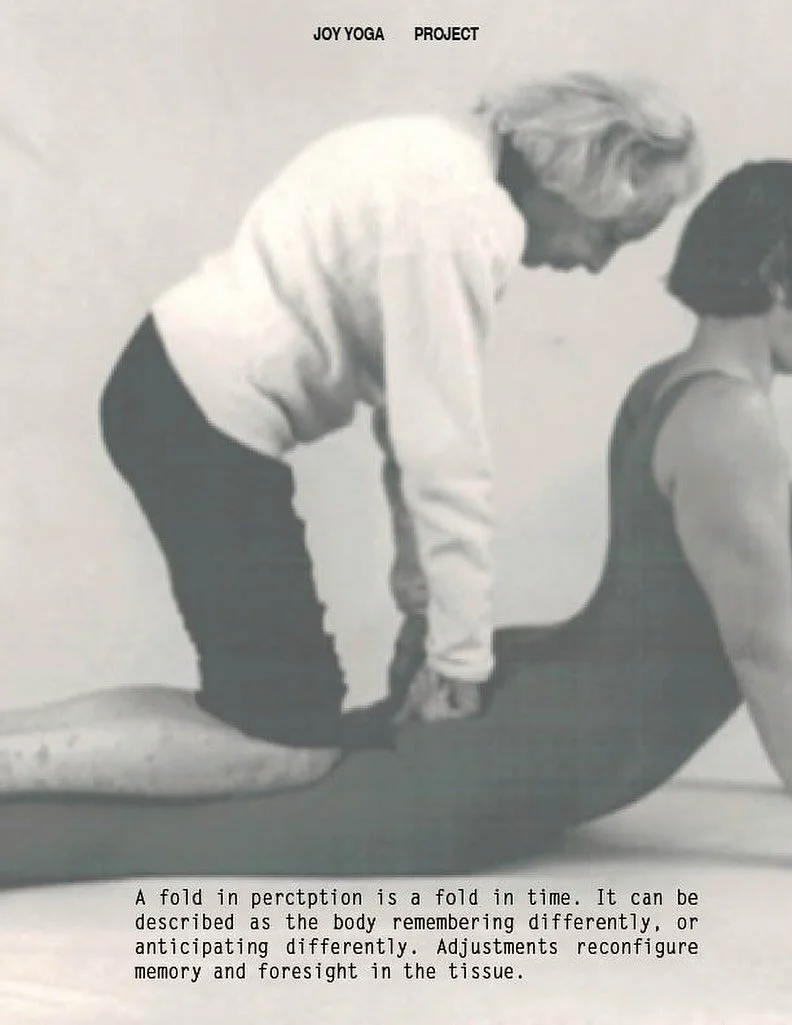

An essential element of Brown’s sacrosanct perspective as it pertains to postural yoga is, as Godfrey Deveroux says, “honoring your capacity, where it is easiest to honor, will increase your capacity, except without pain and injury.” Because our bodies may know something we don’t know. And it may be that our bodies have a wisdom that is more closely aligned with, to quote Vanda Scaravelli, “the urges that motivate me,” or the true essence of me, an essence that is universal and connected to earth and all matter. When my mind is quiet, and I listen, what does my body need from me?

So my practice now, is it your ashanga? Or is it my ashtanga? Is it ashtanga enough?

· I breathe slowly and calmly, stimulating the relaxation response in my nervous system, ujjayi,

· and my breath is coordinated with movement, vinyasa,

· there are bandhas that equalize the forces on my joints, helping to balance and heal tissue and eradicate muscular tension

· there is drishti that aligns my center.

· I am still working to re-sensitize myself and orient from that place, so ahimsa is coming,

· and now that I’m not trying to live up to someone else’s preferences, and I’m listening to rather than telling, there is satya,

· there is an awareness and an honoring of what is happening in my body, so there is aparigraha.

· And as I am now, “the watcher”, there is non-judgmental observation of what is happening, vairayga.

I know there are a lot of other ashtangi’s like me out there, holding their gratitude for the experiences in their body, their yoga has conferred, and every day on their mat aligning the movement in their bodies, with presence. They are meeting people where they are rather than where they want to take them, they are attuned and responding, guiding them to make the discoveries they are ready to make.

As I said earlier, this week I have been doing panchakarma, an Ayurvedic cleanse with Erin (Hannum) and a group of beautiful women from the Shala. Today is the purge. A purge, much like the one that happened in my studio this past month. Erin has been sharing beautiful poems and bits of Ayurvedic wisdom with us all week and this quote from a blog post about how the purge is so potent and necessary, “If there’s no space for the new to enter, you won’t be able to receive.” And “the greater your willingness to let go, change and transform, the greater your ability to invite in new possibilities for yourself.”

Another phrase that keeps popping up in my mind is something my good friend Karen (Sprute-Francovich)says, “ask, what is this posture, moment, situation asking of me?” I guess what this situation is really asking of me is to decide for myself, is yoga just a set of postures in a particular order, or is it much more than that. Those of us who have lived in that set of postures, in that order for years of our lives know it is more than that, but maybe that is the necessary step, but maybe its not.

More and more I see teachers, friends of mine who’ve been to India dozens of times, who’ve spent decades studying, naming their yoga classes and/or approach something other than “insert word yoga”. Often I don’t even see the word yoga anymore, e.g. mindful movement, mindful flow, embodied presence and movement, conscious movement. These teachers have spent years of their lives wholly immersed in a system, Ashtanga, Iyengar, Anusara, and seem to have no choice but to either start from scratch, kicked out of their club, or drift off and go back to a “real” job, when their yoga becomes enough for them but not enough for others.

Years ago I was walking down the street in Burlington, VT on a fridgid night with Kathy (McNames) after the start of a weekend workshop. She was telling me how one of her dear friends, one who had taught at her studio, had left and opened a replica of her school just blocks away. I was horrified and couldn’t imagine it. She told me, “don’t worry Katie, this will happen to you some day too.” And so it has. Getting kicked out of your club stings. But as I go through this cleanse and purge, as I listen to the wise words of the important people in my life, just as the leaves fall off the trees, I am starting to see something about this situation anew, and bare tree limbs hold the promise of new growth, new energy and new light.

And finally, one last thing, my mom said to me last week, in the style of good mom advice, “honey, its time to move on.”

Thank you for all your wise words my friends: Mom, Dad, Mimi, J.Brown, Godfrey Deveroux, Karen Sprute-Francovich, Erin Hannum, Subhan, Matthew Remski, Kathy McNames, Tracy Hodgeman, and posthumously: Vanda Scaravelli, Tom Hanna (And not quoted here but could have been: Gavin Cooley, Buck Holland, Michiko Davis, Chris Conn and Maria Sevilla)

Maybe it looks like this— yoga in living rooms, vegetables shared between friends, warmth, community, and practices that connect. Maybe it’s in the small revelations of finding your knee in your armpit, or your fingers woven behind your head…